To her opponents, Harvard's Claudine Gay’s crime was not knowing her place

"The attacks on Claudine Gay were in response to her success, not her perceived failures.

In her op-ed Wednesday in The New York Times, Claudine Gay, who resigned as the first Black president of Harvard University the day before, after allegations of plagiarism in her scholarly work, writes that “The campaign against me was about more than one university and one leader.” She called the right-wing attacks that led to her resignation “a single skirmish in a broader war to unravel public faith in pillars of American society.”

That may be true, but there’s another way that the attacks on Gay prove to be bigger than her and Harvard. The first-generation American of Haitian parents who became the first Black president in Harvard’s 387-year-old history was subjected to the latest, most prominent example of know-your-place aggression, a backlash of violence — both literal and symbolic, both physical and discursive — that essentially says to people from marginalized groups: Know your place!

Gay has achieved many feats in her career, including rising to the presidency of Harvard after almost two decades of service to the university as a professor who took on various administrative posts and not simply the responsibilities of a productive teacher and scholar. She was recruited to Harvard in 2006 to be a professor of government because her research has shaped scholarly understandings of political behavior.

Many Americans viewed Gay becoming Harvard’s first Black president a sign of progress. Her ascension was positive news, but what exactly are we celebrating when acknowledging such a first? It can’t be that a person of color has finally become qualified to occupy this position. During my almost two decades as a professor, I’ve noticed an unmistakable pattern: Obsessing over whether a candidate of color deserves a spot prevents everyone from noticing that white people get and keep positions without needing to be impressive at all. So, I guess we’re celebrating that the institution finally noticed that white men are not always the best and brightest to be found, despite how relentlessly everyone is told they are.

But, in the same way that the election of the first Black president of the United States resulted in a white backlash, Gay’s ascension to the head of the country’s oldest university bred contempt.

Christopher Rufo, the right-wing ideologue who whipped conservatives into a frenzy over critical race theory, similarly telegraphed his intentions to create a political firestorm to bring down Gay, and he succeeded by accusing her of plagiarism. Her citation practices were not up to the standard I teach my students, so the lack of attribution is serious, but not so serious that it warranted her resignation, especially for someone whose career has, for years, revolved around administering programs and fundraising.

The social media platform X is overrun by people accusing Gay of having been an affirmative action hire, which they use to mean “unqualified.” And Gay said in her Times op-ed Wednesday, “My inbox has been flooded with invective, including death threats. I’ve been called the N-word more times than I care to count.”

Again, we’ve seen this game before. Donald Trump, among others, questioned Barack Obama’s qualifications, not only by saying he was born outside the United States, but also by claiming that he wasn’t smart enough to get into Columbia University, where he majored in political science, or Harvard Law School, where he was the first Black president of the Harvard Law Review. After calling Obama “a terrible student,” Trump said, “Let him show his records.”

To come under fire as Obama and Gay did, no crime or egregious misstep is necessary. They don’t need to have done something wrong for their opponents to believe they aren’t in their “proper” place.

What people call a “microaggression” is actually a form of know-your-place aggression. Admittedly, “know-your-place aggression” is a clunkier term, but it’s more precise because it emphasizes that it’s the success of a person from a marginalized group that inspires the attack. It is especially when people from such groups are succeeding that they must be reminded of their place.

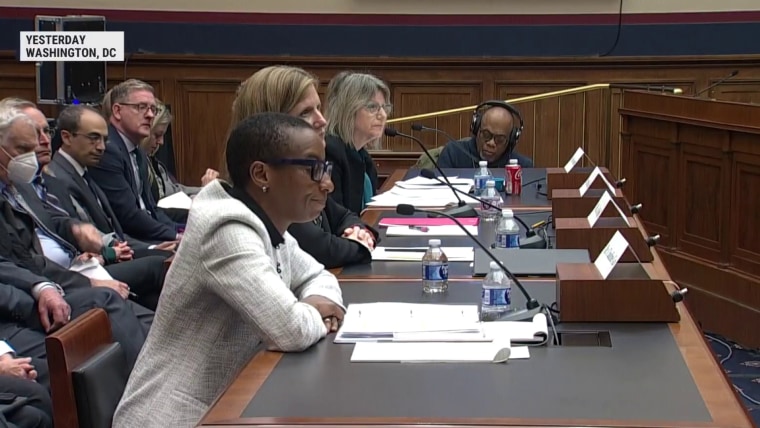

That’s what we saw when Gay was grilled by Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., last month. With Sally Kornbluth at the helm at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Liz Magill at the University of Pennsylvania, it was all women heading universities who were summoned. Still, Stefanik’s raised voice and condescending tone with Gay stood out, making the clip go viral. Women of color, especially Black women, saw and heard on the national stage what we often experience while doing our jobs, no matter what kind of job we have.

Many remain oblivious to know-your-place aggression because it is ingrained in the culture; it reflects what is most commonly said and done. Most people don’t even see it as aggression. Instead, they treat the aggressor as a person with legitimate concerns. Stefanik was counting on us not observing what was happening when she accused Gay of antisemitism. But Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., appropriately responded to Stefanik’s attack on Gay as an attack. He said that, as a Trump supporter, Stefanik has no standing to criticize anyone on antisemitism. "Trump was the one who saw ‘very fine people’ on both sides of the antisemitic riot … in Charlottesville in 2017,” he noted.

Many remain oblivious to know-your-place aggression because it is ingrained in the culture.

And, speaking of standing, what authorized Trump, a reality television star, to question the legitimacy of the first and only Black president of the United States? He has whiteness. That’s it. Trump being white was the only qualification that mattered. Many Americans treated Trump’s questions about Obama as legitimate because the aggressor is white, and the target isn’t.

Know-your-place aggression is as effective as it is because there are people who see it happening but refuse to call it out. The Harvard Corporation, which unanimously accepted Gay’s resignation, reminds me of all the “good” and “decent” people who failed to mobilize as Trump became a political contender by questioning Obama’s credentials. Given what Rufo said he was going to do, Harvard should have been adamant that it would not allow its pioneering president to be brought down by someone acting in such obvious bad faith.

When members of marginalized groups are successful, they will be attacked. They don’t need to have done something wrong to become a target, so expect it. Be ready for it. American culture is designed to resist the success of those who are not cisgender, straight, white and male. When attacks emerge, there’s no value in being a “good” and “decent” person who sits on the sidelines to avoid conflict. When certain people are being reminded of their “proper” place of subordination, allies and accomplices must be proactive, understanding that decency and fairness are not automatic. Especially when you live on stolen land, decency — mere decency — requires deliberate effort.

More from MSNBC Daily

Must reads from Today's list

At Obama’s first inauguration, Rev. Joseph Lowery’s prayer ended with a riff on a blues song, Big Bill Broonzy’s “Black, Brown and White.” He exhorted, “Lord, in the memory of all the saints who from their labors rest, and in the joy of a new beginning, we ask you to help us work for that day when black will not be asked to get in back; when brown can stick around; when yellow will be mellow; when the red man can get ahead, man; and when white will embrace what is right.”

Gay’s short tenure at Harvard shows that Lowery’s prayer remains unanswered."

No comments:

Post a Comment