The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Health

This is so true. I experienced this type of racist treatment at Wellstat Kennestone Hospital in Cobb County Georgia where I was mistreated by the staff and hospital administrators who lied about sending in a prescription by fax for oxycontin which legally they could not have sent in. They refused to treat me after putting in a catheter incorrectly causing a bruise that lasted four years. I talked to medical malpractice attorneys but Republican legislators have made it nearly impossible to sue for this type of treatment. Never see Dr. Nicholas Symbas at Wellstar Hospital.in the Urology Department, He is a racist butcher.

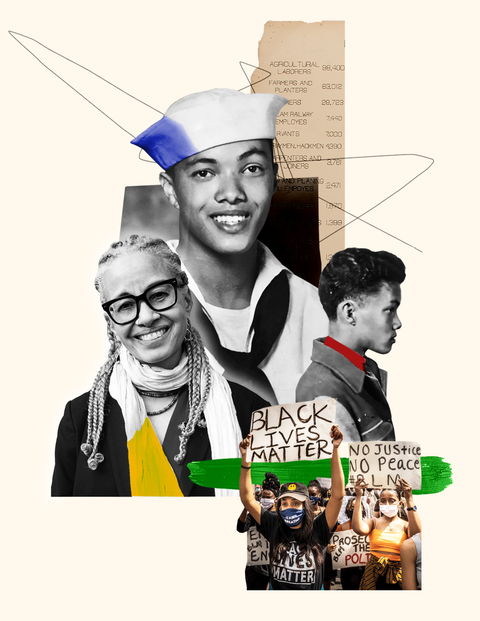

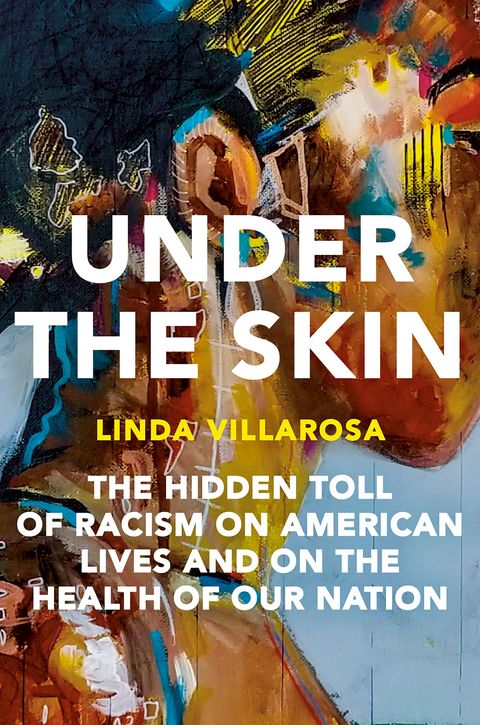

"There has been a historic and continual "Black-white divide in who survives" writes investigative journalist Linda Villarosa in this exclusive excerpt from her new book, Under The Skin.

COURTESY VILLAROSA; GETTY; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; CHLOE KRAMMEL/MH ILLUSTRATION

IN 1999, MY FATHER, a college-educated man who had retired from his job as a manager in a division of a federal agency, became critically ill. In his early seventies, he was diagnosed with colon cancer, and as the disease worsened, he also began to suffer from mild dementia.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

I lived in New York City, across the country from my hometown of Denver, so though my parents had been divorced for years, my mother agreed to manage his care. One day she called me and said, “You need to come home. Your father needs you; he’s in the hospital.”

She instructed me to dress in professional attire and to bring my business cards from The New York Times, where I was the editor of the health pages. When she picked me up at the airport, dressed in extremely corporate attire, looking like the hospital vice president she used to be, I asked her, “What are we doing?” Her reply was blunt: “They are treating your father like a n——; we need to let them see who he is.”

When we arrived at the veterans’ hospital he had insisted on, I was shocked by what I saw: My father—courtly, sophisticated, and always impeccably dressed—was frighteningly thin, disheveled, wearing a dirty hospital gown, his hair uncombed. Worse, he had restraints on his legs. As we walked in, an attendant was speaking to him in a disrespectful hiss. When I pushed past the attendant and leaned down to hug my father, he whispered, “Please get me out of here.”

Everything changed once we arrived. We made them “see” him, beyond his race and the ravages of his illness. My father, who died several months after my mother and I visited him, didn’t deserve “special” treatment because of his class and education; class was the only card my mother and I had to play, so we played it. But like anyone, he should’ve been treated with dignity.

Sadly, not much has changed since then. In my years of reporting on public health and race—including interviewing women and men of all classes whose health has been harmed by the medical system and being embedded for months in some of the most disadvantaged communities in the country—not to mention being a slave-descended African American myself, I have seen a race of people who have been mistreated and misunderstood, ignored and blamed, let down and left to fend for ourselves.

Since the first African enslaved men, women, and children reached American shores, there has been a Black-white divide in who survives, how they live, and who dies, from birth to the end of life. Despite decades of social, economic, and educational progress and what has unquestionably been the rise of a robust Black middle class, racial health disparities have remained intact. Yes, something about being Black is creating a health crisis, and that something is racism.

It is the American problem in need of an American solution. I recently wrote an entire book on about this systemic, institutionalized and tragic topic. And so I am often asked if I feel hopeful about the future. Without a second thought, I continue to answer…

Yes.

Together, America’s racial reckoning and a pandemic that has exposed long-standing racial health inequality have thrown an accelerant on a slow-burning fire of awareness, forcing America to grapple with issues of race and justice and understand the origins of racism and its continued impact on the well-being of people and communities.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

The theories of many racial health equity experts who have been toiling for decades, often behind the scenes, have been thrust into the limelight. Whereas in the past, race was considered a risk factor for a number of health conditions and early death, now it is clear that we must speak the harder truth: it’s not race, something about being Black or something wrong with the Black body, but racism that makes people sick and shortens their lives. Even after science finds a cure for COVID-19, racism in medicine is the harder virus to kill.

But now is the time. The pandemic and the gross injustice of the state-sanctioned killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others have opened hearts and minds across the races to create an opportunity like no other to discuss and confront racism in America; now is the time to create transformative change in health, health care, and health equity in our nation. During the pandemic, California moved ahead of the country, requiring implicit bias training for health-care providers as part of their mandatory continuing education certification beginning in January 2022. The rest of the nation should follow suit.

I am encouraged by the growing recognition that racism in medical care has long existed and continues to cause harm: I see medical societies, universities, hospitals and other institutions, organizations, and individuals grappling with it and working to do better.

Getty Images

We can no longer look away from the impact of the racial health disparities that have been part of the American story since the beginning of our nation. This is not how a just society treats a segment of its population.

As Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, chief of cardiology in the Department of Medicine at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, recently said, “COVID-19 has taken off the Band-Aid that was covering the wound, pointed out how deep it is, and left us no other choice but to finally say, we get it, we see it.”

It’s time for everyone to see things as they really are.

From the book UNDER THE SKIN: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of our Nation. Copyright © 2022 by Linda Villarosa. Published by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC."

No comments:

Post a Comment