Inside Trump’s coronavirus meltdown

What went wrong in the president’s first real crisis — and what does it mean for the US?

When the history is written of how America handled the global era’s first real pandemic, March 6 will leap out of the timeline. That was the day Donald Trump visited the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. His foray to the world’s best disease research body was meant to showcase that America had everything under control. It came midway between the time he was still denying the coronavirus posed a threat and the moment he said he had always known it could ravage America.

Shortly before the CDC visit, Trump said “within a couple of days, [infections are] going to be down to close to zero”. The US then had 15 cases. “One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.” A few days afterwards, he claimed: “I’ve felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic.” That afternoon at the CDC provides an X-ray into Trump’s mind at the halfway point between denial and acceptance.

We now know that Covid-19 had already passed the breakout point in the US. The contagion had been spreading for weeks in New York, Washington state and other clusters. The curve was pointing sharply upwards. Trump’s goal in Atlanta was to assert the opposite.

Wearing his “Keep America Great” baseball cap, the US president was flanked by Robert Redfield, head of the CDC, Alex Azar, the US secretary of health and human services, and Brian Kemp, governor of Georgia. In his 47-minute interaction with the press, Trump rattled through his greatest hits.

He dismissed CNN as fake news, boasted about his high Fox News viewership, cited the US stock market’s recent highs, called Washington state’s Democratic governor a “snake” and admitted he hadn’t known that large numbers of people could die from ordinary flu. He also misunderstood a question on whether he should cancel campaign rallies for public health reasons. “I haven’t had any problems filling [the stadiums],” Trump said.

What caught the media’s attention were two comments he made about the disease. There would be four million testing kits available within a week. “The tests are beautiful,” he said. “Anybody that needs a test gets a test.”

Ten weeks later, that is still not close to being true. Fewer than 3 per cent of Americans had been tested by mid-May. Trump also boasted about his grasp of science. He cited a “super genius” uncle, John Trump, who taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and implied he inherited his intellect. “I really get it,” he said. “Every one of these doctors said, ‘How do you know so much about this?’ Maybe I have a natural ability.” Historians might linger on that observation too.

What the headlines missed was a boast that posterity will take more seriously than Trump’s self-estimated IQ, or the exaggerated test numbers (the true number of CDC kits by March was 75,000). Trump proclaimed that America was leading the world. South Korea had its first infection on January 20, the same day as America’s first case, and was, he said, calling America for help. “They have a lot of people that are infected; we don’t.” “All I say is, ‘Be calm,’” said the president. “Everyone is relying on us. The world is relying on us.”

He could just as well have said baseball is popular or foreigners love New York. American leadership in any disaster, whether a tsunami or an Ebola outbreak, has been a truism for decades. The US is renowned for helping others in an emergency.

In hindsight, Trump’s claim to global leadership leaps out. History will mark Covid-19 as the first time that ceased to be true. US airlifts have been missing in action. America cannot even supply itself.

South Korea, which has a population density nearly 15 times greater and is next door to China, has lost a total of 259 lives to the disease. There have been days when America has lost 10 times that number. The US death toll is now approaching 90,000.

What has gone wrong? I interviewed dozens of people, including outsiders who Trump consults regularly, former senior advisers, World Health Organization officials, leading scientists and diplomats, and figures inside the White House. Some spoke off the record.

Again and again, the story that emerged is of a president who ignored increasingly urgent intelligence warnings from January, dismisses anyone who claims to know more than him and trusts no one outside a tiny coterie, led by his daughter Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner – the property developer who Trump has empowered to sideline the best-funded disaster response bureaucracy in the world.

People often observed during Trump’s first three years that he had yet to be tested in a true crisis. Covid-19 is way bigger than that. “Trump’s handling of the pandemic at home and abroad has exposed more painfully than anything since he took office the meaning of America First,” says William Burns, who was the most senior US diplomat, and is now head of the Carnegie Endowment.

“America is first in the world in deaths, first in the world in infections and we stand out as an emblem of global incompetence. The damage to America’s influence and reputation will be very hard to undo.”

The psychology behind Trump’s inaction on Covid-19 was on display that afternoon at the CDC. The unemployment number had come out that morning. The US had added 273,000 jobs in February, bringing the jobless rate down to a near record low of 3.5 per cent. Trump’s re-election chances were looking 50:50 or better. The previous Saturday, Joe Biden had won the South Carolina primary. But the Democratic contest still seemed to have miles to go. Nothing could be allowed to frighten the Dow Jones.

Any signal that the US was bracing for a pandemic – including taking actual steps to prepare for it – was discouraged.

“Jared [Kushner] had been arguing that testing too many people, or ordering too many ventilators, would spook the markets and so we just shouldn’t do it,” says a Trump confidant who speaks to the president frequently. “That advice worked far more powerfully on him than what the scientists were saying. He thinks they always exaggerate.”

Stephen Moore of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank, who talks regularly to Trump and is a campaign adviser, says the mood was borderline ecstatic in early March. “The economy was just steaming along, the stock market was firing on all cylinders and that jobs report was fantastic,” says Moore. “It was almost too perfect. Nobody expected this virus. It hit us like a meteor or a terrorist attack.”

People in Trump’s orbit are fond of comparing coronavirus to the 9/11 attacks. George W Bush missed red flags in the build-up to al-Qaeda’s Twin Towers attacks. But he was only once explicitly warned of a possible plot a few weeks before it happened. “All right, you’ve covered your ass,” Bush reportedly told the briefer.

At some point, Congress is likely to establish a body like the 9/11 Commission to investigate Trump’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. The inquiry would find that Trump was warned countless times of the epidemic threat in his presidential daily briefings, by federal scientists, the health secretary Alex Azar, Peter Navarro, his trade adviser, Matt Pottinger, his Asia adviser, by business friends and the world at large. Any report would probably conclude that tens of thousands of deaths could have been prevented – even now as Trump pushes to “liberate” states from lockdown.

“It is as though we knew for a fact that 9/11 was going to happen for months, did nothing to prepare for it and then shrugged a few days later and said, ‘Oh well, there’s not much we can do about it,’” says Gregg Gonsalves, a public health scholar at Yale University. “Trump could have prevented mass deaths and he didn’t.”

In fairness, other democracies, notably the UK, Italy and Spain, also wasted time failing to prepare for the approaching onslaught. Whoever was America’s president might have been equally ill-served by Washington infighting.

The CDC has been plagued by mishap and error throughout the crisis. The agency spent weeks trying to develop a jinxed test when it could simply have imported WHO-approved kits from Germany, which has been making them since late January. “The CDC has been missing in action,” says a former senior adviser in the Trump White House. “Because of the CDC’s errors, we did not have a true picture of the spread of the disease.”

Here again, though, Trump’s stamp is clear. It was Trump who chose Robert Redfield to head the CDC in spite of widespread warnings about the former military officer’s controversial record. Redfield led the Pentagon’s response to HIV-Aids in the 1980s. It involved isolating suspected soldiers in so-called HIV Hotels. Many who tested positive were dishonourably discharged. Some committed suicide.

A devout catholic, Redfield saw Aids as the product of an immoral society. For many years, he championed a much-hyped remedy that was discredited in tests. That debacle led to his removal from the job in 1994.

“Redfield is about the worst person you could think of to be heading the CDC at this time,” says Laurie Garrett, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist who has reported on epidemics. “He lets his prejudices interfere with the science, which you cannot afford during a pandemic.”

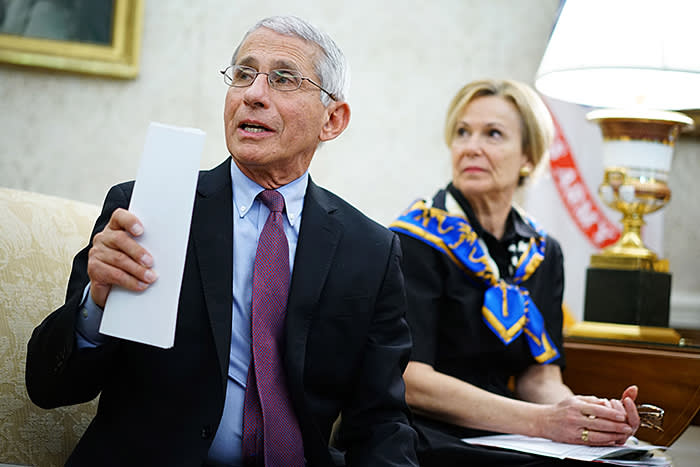

One of the CDC’s constraints was to insist on developing its own test rather than import a foreign one. Dr Anthony Fauci – the infectious disease expert and now household name – is widely known to loathe Redfield, and vice versa. That meant the CDC and Fauci’s National Institutes of Health were not on the same page. “The last thing you need is scientists fighting with each other in the middle of an epidemic,” says Dr Kenneth Bernard, who set up a previous White House pandemic unit in 2004, which was scrapped under Barack Obama and later revived after Ebola struck in 2014. .

The scarcity of kits meant that the scientists lacked a picture of America’s rapidly spreading infections. The CDC was forced to ration tests to “persons under investigation” – people who had come within 6ft of someone who had either visited China or been infected with Covid-19 in the previous 14 days. Most were denied. Few could prove that they had met either criterion. This was at a time when several countries, notably Germany, Taiwan and South Korea, gave access to on-the-spot tests, including at drive-through centres – an option most Americans still lack.

“You’ve been commuting by train or subway into New York every day, you show up sick in the clinic and they refuse to test you because you can’t prove you’ve been within 6ft of someone with Covid-19,” says the former adviser. “You’ve probably been close to half a million people in the previous two weeks.”

Restrictions on testing narrow the options. “Once you get to one per cent prevalence in any community, it is too late for non-pharmaceutical interventions to work,” says Tom Bossert, who led the since-disbanded White House pandemic office before he was ejected in 2018 by John Bolton, Trump’s then national security adviser.**

By March 11, just five days after Trump’s CDC visit, the reality was beginning to seep through. In an Oval Office broadcast, Trump banned travel from most of Europe, which expanded the partial ban he put on China in February. Two days later, he declared a national emergency. Even then, however, he insisted America was leading the world. “We’ve done a great job because we acted quickly,” he said. “We acted early.

Over the next 48 hours, however, something snapped in Trump’s mind. Citing a call with one of his sons, Trump said on March 16: “It’s bad. It’s bad… They think August [before the disease peaks]. Could be July. Could be longer than that.”

Eleven days later, Boris Johnson, Britain’s prime minister contracted Covid-19. The disease nearly killed him. That was Johnson’s road-to-Damascus. Many hoped Trump had had a similar conversion. If so, it did not last long. The next week, he was saying that America should reopen by Easter on April 12. “I was one of the ones advising him to make it ‘Resurrection Sunday,’” says Moore. “I told him then what I think now, that this lockdown is causing more deaths and misery than the disease itself.”

Trump’s mindset became increasingly surreal. He began to tout hydroxychloroquine as a cure for Covid-19. On March 19, at a regular televised briefing, which he conducted daily for five weeks, often rambling for more than two hours, he depicted the antimalarial drug as a potential magic bullet. It could be “one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine”, he later tweeted.

The president’s leap of faith, which was inspired by Fox News anchors, notably Laura Ingraham, and his lawyer Rudy Giuliani, none of whom have a medical background, turned Washington’s bureaucracy upside down. Scientists who demurred were punished. In April, Rick Bright, the federal scientist in charge of developing a vaccine – arguably the most urgent role in government – was removed after blocking efforts to promote hydroxychloroquine.

Most clinical trials have shown the drug has no positive impact on Covid-19 patients and can harm people with heart problems. “I was pressured to let politics and cronyism drive decisions over the opinions of the best scientists we have in government,” Bright said in a statement.

In a whistleblower complaint, he said he was pressured to send millions of dollars worth of contracts to a company controlled by a friend of Jared Kushner. When he refused, he was fired. The US Department of Health and Human Services denied Bright’s allegations.

Other scientists have taken note of Bright’s fate. During the Ebola outbreak in 2014, when Obama’s administration sent 3,000 US military personnel to Africa to fight the epidemic, the CDC held a daily briefing about the state of progress. It has not held one since early March. Scientists across Washington are terrified of saying anything that contradicts Trump.

“The way to keep your job is to out-loyal everyone else, which means you have to tolerate quackery,” says Anthony Scaramucci, an estranged former Trump adviser, who was briefly his White House head of communications. “You have to flatter him in public and flatter him in private. Above all, you must never make him feel ignorant.”

An administration official says advising Trump is like “bringing fruits to the volcano” – Trump being the lava source. “You’re trying to appease a great force that’s impervious to reason,” says the official.

When Trump suggested in late April that people could stop Covid-19, or even cure themselves, by injecting disinfectant, such as Lysol or Dettol, his chief scientist, Deborah Birx, did not dare contradict him. The leading bleach companies issued statements urging customers not to inject or ingest disinfectant because it could be fatal. The CDC only issued a cryptic tweet advising Americans to: “Follow the instructions on the product label.”

“I can’t even get my calls returned,” says Garrett. “The CDC has led the response to every disease for decades. Now it has vanished from view.” A former senior Trump official says: “People turn into wusses around Trump. If you stand up to him, you’ll never get back in. What you see in public is what you get in private. He is exactly the same.”

America’s foreign partners have had an equally sharp reminder of Trump’s way of doing business. Few western leaders are as ideologically aligned with Trump as Scott Morrison, Australia’s prime minister. Early into the epidemic, Morrison created a national cabinet that meets at least once a week. It includes every state premier of the two main parties. Morrison’s unity cabinet projects an air of bipartisan resolve in a country that has lost just under 100 people to coronavirus in three months. Some days, America has lost more people to it every hour.

Trump, by contrast, plays US state governors against each other, much as he does with his staff. Republican states have received considerably more ventilators and personal protective equipment per capita than Democratic states, in spite of having far lower rates of hospitalisation. Trump says America is fighting a war against Covid-19. In practice, he is stoking national disunity. “It’s like saying to the governors that each state has to produce its own tanks and bullets,” says Bernard. “You’re on your own. It’s not my responsibility.”

Trump’s dog-eat-dog instinct has been just as strong abroad as at home. A meeting of G7 foreign ministers in March failed to agree on a statement after Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state, insisted they brand it the “Wuhan virus”. America declined to participate in a recent summit hosted by Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, to collaborate on a vaccine.

Most dramatically, Trump has suspended US funding of the WHO, which he says covered up for China’s lying. The WHO confirms that Trump met the then director-general designate, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in the Oval Office in June 2017, shortly before he took up the role. Trump supported his candidacy.

Other critics say the Geneva-based body was too ready to take Beijing’s word at face value. There is some truth to that claim. “They were too scared of offending China,” says Bernard, who was America’s WHO director for two years. But its bureaucratic timidity did not stop other countries from taking early precautions.

Trump alleged the WHO’s negligence had increased the world’s death rate “twenty-fold”. In practice, the body must always abide by member state limits, especially the big ones, notably the US and China. That is the reality for all multilateral bodies. The WHO nevertheless declared an international emergencysix weeks before Trump’s US announcement. WHO officials say Trump’s move has badly hindered its operations.

“You don’t turn off the hose in the middle of the fire, even if you dislike the fireman,” says Bernhard Schwartländer, chief of staff at the WHO. “This virus threatens every country in the world and will exploit any crack in our resolve.” The body, in other words, has fallen victim to US-China hostility.

Blaming America’s death rate on China and the WHO could well help Trump’s re-election campaign. Many voters are all too ready to believe the US is a victim of nefarious global forces. Garrett, who is a former senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, cites Inferno, a lesser-known novel by Dan Brown, author of the best-selling Da Vinci Code, in which the WHO plays a dastardly role.

One of its leading characters is a biologist at the CFR. During a pandemic, she kidnaps the head of the WHO and puts him in the think-tank’s basement. He is rescued by a WHO military team that swoops in on the body’s C-130 jet. In reality, the agency has no police powers at all. “We are not like Interpol,” says Schwartländer. The WHO can no more insist on going into Wuhan to investigate the origins of Covid-19 than it can barge into Atlanta to investigate the CDC’s delay in producing a test.

Both the US and China have spread outlandish rumours about the other. Some Chinese officials have circulated the groundless conspiracy theory that the US army planted the virus in Wuhan at an athletics event last year. Trump administration officials, including Pompeo, have repeatedly suggested Covid-19 originated from a bat-to-human transmission in Wuhan’s virology lab.

Last month, Australia called for an international inquiry into the disease’s origins. “Australia’s goal was to defuse conspiracy theories in both China and America,” says Michael Fullilove, head of the Lowy Institute, Australia’s largest think-tank.

Days later, Australia’s Daily Telegraph, a tabloid owned by Rupert Murdoch, ran an apparent scoop that the “five eyes” – the intelligence agencies of the US, the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand – had concluded the disease came from the Wuhan lab, whether by accident or design. It appears the story had no substance. Fauci and other scientists say the pathogen almost certainly came from a wet market in Wuhan. No “five eyes” dossier existed.

According to a five eye senior intelligence officer and a figure close to Australia’s government, the Daily Telegraph story probably came from the US embassy in Canberra. There was no chance after its publication that Beijing would agree to an international probe. The report damaged Australia’s hopes of defusing US-China tensions. “We used to think of America as the world’s leading power, not as the epicentre of disease,” says Fullilove, who is an ardent pro-American. “We increasingly feel caught between a reckless China and a feckless America that no longer seems to care about its allies.”*

So where does the American chapter of the plague go from here? Early into his partial about-turn, Trump said scientists told him that up to 2.5 million Americans could die of the disease. The most recent estimates suggest 135,000 Americans will die by late July. That means two things.

First, Trump will tell voters that he has saved millions of lives. Second, he will continue to push aggressively for US states to lift their lockdowns. His overriding goal is to revive the economy before the general election. Both Trump and Kushner have all but declared mission accomplished on the pandemic. “This is a great success story,” said Kushner in late April. “We have prevailed,” said Trump on Monday.

Economists say a V-shaped recovery is unlikely. Even then it could be two Vs stuck together – a W, in other words. The social mingling resulting from any short-term economic reopening would probably come at the price of a second contagious outburst. As long as the second V began only after November, Trump might just be re-elected.

“From Trump’s point of view, there is no choice,” says Charlie Black, a senior Republican consultant and lobbyist. “It is the economy or nothing. He can’t exactly run on his personality.” Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist, had a slightly different emphasis: “Trump’s campaign will be about China, China, China,” he says. “And hopefully the fact that he rebooted the economy.”

In the meantime, Trump will probably continue to dangle the prospect of miracle cures. Every week since the start of the outbreak, he has said a vaccine is just around the corner. His latest estimate is that it will be ready by July. Scientists say it will take a year at best to produce an inoculation. Most say 18 months would be lucky. Even that would break all records. The previous fastest development was four years for mumps in the 1960s.

For the time being, Trump has been persuaded to cease his daily briefings. The White House internal polling shows that his once double-digit lead over Biden among Americans over 65 has been wiped out. It turns out retirees are no fans of herd immunity.

Friends of the president are trying to figure out how to return life to normal without provoking a new death toll. After an initial rally in March, Trump’s poll numbers have been steadily dropping over the last month. For the next six months, America’s microbial fate will be in the hands of its president’s erratic re-election strategy. There is more than a whiff of rising desperation.

“Trump is caught in a box which keeps getting smaller,” says George Conway, a Republican lawyer who is married to Kellyanne Conway, Trump’s senior counsellor. “In my view he is a sociopath and a malignant narcissist. When a person suffering from these disorders feels the world closing in on them, their tendencies get worse. They lash out and fantasise and lose any ability to think rationally.” Conway is known for taunting Trump on Twitter (to great effect, it should be added: Trump often retaliates).

Yet without exception, everyone I interviewed, including the most ardent Trump loyalists, made a similar point to Conway. Trump is deaf to advice, said one. He is his own worst enemy, said another. He only listens to family, said a third. He is mentally imbalanced, said a fourth. America, in other words, should brace itself for a turbulent six months ahead – with no assurance of a safe landing.”

No comments:

Post a Comment