A black woman faces prison because of a Jim Crow-era plan to ‘protect white voters’

Lanisha Bratcher voted in the 2016 presidential election. Three years later she was arrested because she had broken a law she didn’t know about.

Lanisha Bratcher was finishing breakfast at home one morning at the end of July when there was a knock on her door. She had been discharged from the hospital the night before following a miscarriage that left her mourning the loss of her child.

Her partner opened the door – it was the police. They burst into their North Carolinahome “like the Dukes of Hazzard”, Bratcher said. There was a warrant out for her arrest, they told her. Bratcher had no idea what for.

Her crime? Voting in the 2016 presidential election.

Bratcher faces up to 19 months in prison because she did not realize she had actually been stripped of the right to vote. Her lawyer says she’s being punished based on a Jim Crow-era law that was intended to disenfranchise African Americans.

Bratcher was on probation after being convicted of assault and North Carolina law mandates that people convicted of felonies can only vote once they complete their criminal sentences, including probation and parole, entirely.

Documents obtained by the Guardian show that a prosecutor brought charges against Bratcher even though state officials said she may have illegally voted unintentionally. The decision also came after a report in which state officials recognized there were serious problems in the system in place to inform convicted felons of their voting rights.

The state’s policy of banning people convicted of felonies from voting is rooted in a late 19th century effort by North Carolina Democrats to limit voting power of newly-enfranchised African Americans as whole. In 1898, the North Carolina Democratic party spoke of the need “to rescue the white people of the east from the curse of negro domination”.

Since then, North Carolina lawmakers have tweaked the law, but its core – stripping felons of their voting rights while they serve criminal sentences – remains in place.

John Carella, Bratcher’s lawyer, noted the vast majority of the people caught up in the law are African American. “A law that is intended to racially discriminate against a group is unconstitutional,” he said. “We also know it continues to work that way in its modern application to the 2016 election.”

Carella argues that the goal is to dissuade black voters from going to the polls. That could make a big difference in North Carolina, a fiercely politically competitive state expected to play a key role in the 2020 election.

In Bratcher’s case, it seems to have worked. She’s not sure if she’ll ever vote again, even once she’s legally allowed to.

“It seems really dangerous,” she said.

‘Strict liability’

Bratcher grew up in Hoke county, where she readily acknowledges she had a rocky past, sometimes getting in trouble with law enforcement. In 2013, she and her sister got into a fight with some other people and Bratcher was charged with assault with a deadly weapon.

She had since been working hard to turn a page – moving to Wake county with her husband and two daughters and trying to get a promotion at work.

During the March 2016 primary, Bratcher registered to vote, according to election records. She said that at that time, nobody had told her she couldn’t vote.

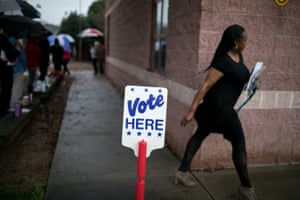

Later that year, her church had an event where they hosted a dinner and took people to the polls. So Bratcher went with her mother to vote during the early voting period before election day.

“I had no intention to trick anybody or be malicious or any kind of way,” she said. “If you expect us to know that we should know we should not do something, then we should not be on the list or even allowed to do it.”

Americans lose the right to vote if they are convicted of a felony in 48 of the 50 states. But each of those states has widely different policies on when and if felons can vote again.

If someone votes while they are serving a criminal sentence, it is a so-called “strict liability” felony in North Carolina. That means that prosecutors don’t have to prove Bratcher and other people convicted of felonies intended to vote illegally in order to convict them.

This statute was designed after the civil war as a reaction to growing African American political power in the state, said Gary Freeze, a history and American studies professor at Catawba College in North Carolina.

“White supremacists did not want [another] reform effort – hence the severe penalty for those who could be proven to be voting with a criminal background,” he wrote in an email.

When lawmakers passed the felon-voting law, they were open about their racial intent. The 1898 Democratic handbook in the state talked about voting restrictions necessary “to protect the white voters of the State against having their honest votes off-set by illegally and fraudulently registered negro votes”. One cartoon in a local newspaper featured a picture of a “white supremacy plum”, with a caption encouraging voters to “pluck it” on election day in 1898. Another cartoon featured a vampire flying over North Carolina with the words “negro rule” on its wings.

And in 1903, Charles Aycock, then governor of the state, openly spoke about how disenfranchisement was part of solving the “negro problem”. “I am inclined to give you our solution of this problem. It is, first, as far as possible, under the fifteenth amendment, to disfranchise him; after that, let him alone; quit writing about him; quit talking about him,” he said.

Carella argues the discriminatory law is still at work – of 441 people investigated for possibly voting with a felony in the 2016 election, 68% were black.

That high number exceeds both the percentage of African Americans registered to vote and the proportion on probation and parole. At the end of 2016, African Americans made up about 46% of convicted felons on parole or probation in the state. They made up about 22% of all registered voters.

The North Carolina felon voting law has not only been discriminatory, but also confusing. A little over four months after the 2016 election, the state board of elections released a report finding there wasn’t a standardized process for informing people on probation they couldn’t vote.

Officials have since updated the state voter registration form to make it clearer that people can’t vote on probation or parole. They also updated a pamphlet people receive when they are released from prison. In its letter to Bratcher’s prosecutor, the state board said it didn’t have the resources to investigate the particular circumstances of Bratcher’s case.

“I’ve never heard of a judge informing a convicted individual of the loss of voting rights or the process by which these can be restored,” said Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice advocacy group. He called the many cases in which people get prosecuted for unintentionally voting illegally “disturbing”.

More than 400 convicted felons were suspected of voting in North Carolina in the 2016 elections. District attorneys have the discretion on whether to advance the prosecution, and are either reviewing charges or pursuing them in about half of the cases, according to state-level data obtained by The Guardian.

Bratcher is among four people with felonies in her county – all of whom are black – who have been indicted for illegally voting in 2016.

Kristy Newton, the district attorney in Hoke county, declined to comment on the case because it was still pending.

Life upended

Bratcher’s case isn’t the first time a voter fraud case like this has come under scrutiny in North Carolina. In 2018, 12 people with felony convictions in the state were prosecuted for illegal voting. The decision to prosecute the group – which came to be known as the Alamance 12 – drew national outrage because they also said they didn’t know they were ineligible.

Civil rights groups are also challenging the state’s felon voting law, saying it unconstitutionally disenfranchises nearly 70,000 people in the state who are on parole or probation for a felony. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, won the state’s 2016 gubernatorial election by a little over 10,000 votes.

Getting charged with voter fraud upended Bratcher’s life. It took an hour and a half to drive each way for court appearances. Even though she was on the verge of advancing at her factory job for Burt’s Bees, the court appearances caused her to miss work. She eventually left her job, and said the pending criminal charge against her made it harder for her to find a new one, she said.

There was also the embarrassment of dealing with a new criminal charge. She has two daughters, aged 12 and seven, and she doesn’t want them to know about her voter fraud case. But after she was arrested, the Hoke county sheriff’s office announced the voter fraud charges on Facebook and mugshots of Bratcher and her co-defendants appeared in the local news. Family and friends and people from her church began calling her asking what she had done.

“I was at a better place in my life. I had a different mindset. I don’t have any barriers, I don’t have any borders, I don’t have any walls up. I’m free and now I can be able to meet my full potential,” she recalls feeling at the time. “But then the walls came tumbling down.”

She likened the experience to a bucket of crabs – when one crab tries to escape, she said, another one will pull it back in. “I fought so hard to try and come from under that,” she said.

A racist legacy

Carella argued in court documents filed earlier this year that Bratcher’s case should be thrown out because the law she is being prosecuted under is discriminatory against African Americans. He said the statute remains as racist as it was at the turn of the 20th century.

The judge in Bratcher’s case could agree with Carella and throw out the case. If not, it will move towards a criminal trial.

Torris Jones, Bratcher’s husband, said he understands her new apprehension about voting, but sees it differently.

“If you don’t vote again, then the law would have done exactly what it was supposed to do, which is to suppress your vote,” he said. “If they’ve got you afraid, then the law did what it’s supposed to do.”

No comments:

Post a Comment