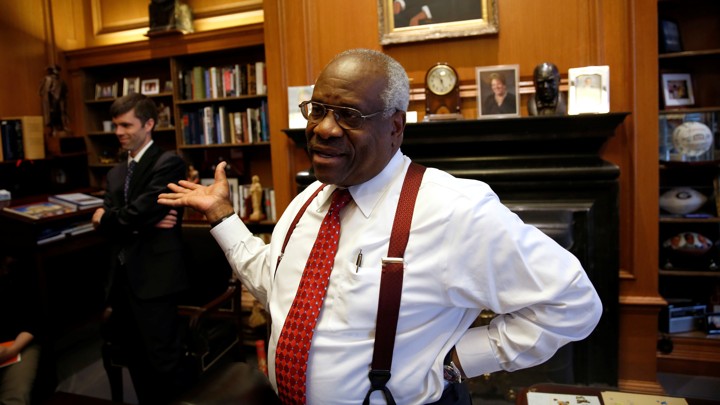

"In Tuesday’s ruling on Indiana’s abortion law, Justice Clarence Thomas took the national debate over the right to choose to a dark new place: eugenics. His 20-page concurring opinion included an extensive discussion of the eugenics movement of the early 20th century. Thomas argued that as the justices consider abortion going forward, they should pay more attention to its potential to become a “tool of eugenic manipulation.”

In making his argument, Thomas cited my book Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck repeatedly. (He also cited an article I wrote about Harvard’s ties to eugenics). I don’t want to appear ungrateful: It’s an honor to be relied on by the highest court in the land, and these days, nonfiction authors appreciate just being read at all. But Thomas used the history of eugenics misleadingly, and in ways that could dangerously distort the debate over abortion.

Thomas’s opinion came as an addendum to a decision that sidestepped the most difficult issues raised by the Indiana law. Although the Court upheld Indiana’s requirement that abortion providers bury or cremate fetal remains, it refused to reinstate another part of the law that banned abortions solely because of the sex or disability of the fetus. The New York Times reported that the decision was “an apparent compromise.” It says a lot about where abortion law is today that upholding a law requiring a woman to allow her aborted fetus to be given the funerary rites of a dead child—and possibly to pay a hefty bill for it—now counts as a “compromise.”

Thomas did not object to the Court’s ruling, but he offered up his lengthy treatise on eugenics to help the Court when it considers more laws like Indiana’s in the future. His motivation was apparently to put a new weapon in the arsenal of the anti-abortion movement. If you do not buy the argument that abortion ends a human life, how about the idea that it is an attempt to restrict reproduction in order to “improve” the human race?

Thomas relied on a kind of historical guilt-by-association. “The foundations for legalizing abortion in America were laid during the early 20th century birth-control movement,” he wrote. The birth-control movement, in turn, “developed alongside the American eugenics movement.” Therefore, he suggested, abortion is inseparable from America’s history of eugenics.

In supporting his claim, Thomas cited real history that is not particularly relevant to abortion. It is true, as Thomas said, that Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, supported eugenics and that she had some pretty offensive views. (Anyone who doubts that should read what Sanger had to say about “slum mothers” in her book The Pivot of Civilization.) It is also true that Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which sharply diminished immigration of Eastern European Jews and Italians, in part out of a desire to enforce racial “purity.” And Thomas is correct that the Supreme Court played a lamentable role in the eugenics era with its 1927 ruling in Buck v. Bell, the subject of my book. The Court upheld a Virginia law that authorized the state to sterilize people it considered unworthy of reproducing, and it allowed the state to sterilize Carrie Buck, the poor young woman at the center of the case.

None of this was about abortion, however. The most prominent American eugenicists did not support abortion. As the intellectual leader of the movement, Harry Laughlin—the head of the infamous Eugenics Record Office, on Long Island—put it, the goal of modern eugenics was “preventing the procreation of defectives rather than destroying them before birth.” In fact, at the height of the eugenics movement, abortion was outlawed throughout the United States, so it was not going to be the mechanism for changing the American gene pool.

The American eugenics movement overwhelmingly supported not abortion but forced sterilization. More than half of the states adopted laws like Virginia’s, which allowed the state to sterilize people it deemed unworthy of reproducing because of physical or mental deficiencies or other “failings,” such as alcoholism or poverty.

Between eugenic sterilization and abortion lie two crucial differences: who is making the decision, and why they are making it. In eugenic sterilization, the state decides who may not reproduce, and acts with the goal of “improving” the population. In abortion, a woman decides not to reproduce, for personal reasons related to a specific pregnancy.

That is ultimately where Thomas’s argument falls apart. A woman in Indiana who has an abortion because the child will be born with a severe disability is not acting eugenically—she is not trying to uplift the human race. She is simply deciding that she does not want to give birth to a child who, for example, would die in infancy after a brief life of extreme pain.

Thomas’s concurring opinion is an example of a common form of argumentation: the false analogy to a universally acknowledged historical atrocity. Extremists in the anti-abortion movement do this a great deal—for example, by comparing abortion to the Holocaust. Of course, this form of argumentation is not limited to the abortion debate; a top technology adviser to President Donald Trump once said, “The demonization of carbon dioxide is just like the demonization of the poor Jews under Hitler.”

Carbon dioxide’s problems are not analogous to the Jews’ problems under Hitler, and allowing a woman to decide whether to give birth is not analogous to the Final Solution—or to the misdeeds of the eugenics era. When the time comes for the Court to once again consider a statute like Indiana’s, Thomas’s eugenics history should not be its guide.

Despite all of this, I will admit to having been a little bit pleased when I read Thomas’s opinion—and not only because, as a journalist friend said, the references to Imbeciles were “good for the brand.” Americans today know too little about the American eugenics movement. This history speaks powerfully to our time, although not in the way Thomas suggested.

Eugenics may indeed be making a comeback. Representative Steve King, the Iowa Republican and immigration hard-liner, echoed the concerns of the movement when he tweeted, “We can’t restore our civilization with somebody else’s babies.” So did Trump when he reportedly said that the United States needs fewer immigrants from “shithole countries” and “more people from places like Norway.” And so did white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, when they chanted, “Jews will not replace us.”

Thomas is absolutely right that we need to remember our eugenics past and make sure that we do not make the same mistakes again. He is absolutely wrong that individual women making independent decisions about their pregnancies are the eugenicists of our time."

Clarence Thomas Knows Nothing of My Work

No comments:

Post a Comment