A collection of opinionated commentaries on culture, politics and religion compiled predominantly from an American viewpoint but tempered by a global vision. My Armwood Opinion Youtube Channel @ YouTube I have a Jazz Blog @ Jazz and a Technology Blog @ Technology. I have a Human Rights Blog @ Law

Thursday, May 30, 2019

Opinion | Decoding Robert Mueller

"By The Editorial BoardMay 29, 2019

After two years of frenzied speculation, the special counsel Robert Mueller at last spoke publicly about his investigation of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 elections. His statement Wednesday was considered and temperate, its delivery passionless, if not robotic. If you tuned out for a moment — and who could blame you — you might have missed the import of the messages encoded in Mr. Mueller’s cautious language. Yet if you listened carefully, both for what he said and what he did not say, the statement was quite clarifying. Below are Mr. Mueller’s key points, translated.

After briefly reviewing his mandate, as laid out by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, Mr. Mueller announced that his team was “formally closing the special counsel’s office,” that he was leaving the Justice Department and that “beyond these few remarks, it is important that the office’s written work speak for itself.”

Translation: I’m done with this political circus. To understand my findings, read my report. Please don’t ask me to testify.

Mr. Mueller was careful to emphasize that if his office “had confidence that the president clearly did not commit a crime, we would have said so.”

Translation: There’s a decent chance the president committed a crime.

He went on to point out that “under longstanding department policy, a president cannot be charged with a federal crime while he is in office. That is unconstitutional.” He added, “Charging the president with a crime was therefore not an option we could consider.”

Translation: This was not about a lack of evidence, and it certainly doesn’t amount to the “exoneration” President Trump has claimed. We couldn’t indict because we weren’t allowed to indict. We did, however, draw Congress a detailed map of the multiple ways that this president may have obstructed justice.

Mr. Mueller noted that department policy “explicitly permits the investigation of a sitting president, because it is important to preserve evidence while memories are fresh and documents available.”

Translation: Presidents don’t stay in office forever. Who knows how this information might come in handy to prosecutors in a couple of years?

He said that “the Constitution requires a process other than the criminal justice system to formally accuse a sitting president of wrongdoing.”

Translation: It’s called an impeachment inquiry.

Further on obstruction, Mr. Mueller said, “When a subject of an investigation obstructs that investigation or lies to investigators, it strikes at the core of their government’s effort to find the truth and hold wrongdoers accountable.”

Translation: Did you notice I said “when” not “if”? Obstruction happened; I’m being coy about who I suspect committed it.

Mr. Mueller acknowledged that, when it came to releasing the report, he and William Barr, the attorney general, had different visions of how to do so. Even so, he said, “I certainly do not question the attorney general’s good faith in that decision.”

Translation: Mr. Barr made a bad decision, but I’m not going to directly criticize his initial misleading summary of the report because he made the report largely public.

As for where things go from here, Mr. Mueller had a message for Congress:

“Now, I hope and expect this to be the only time that I will speak to you in this manner. I am making that decision myself. No one has told me whether I can or should testify or speak further about this matter. There has been discussion about an appearance before Congress. Any testimony from this office would not go beyond our report. It contains our findings and analysis and the reasons for the decisions we made. We chose those words carefully, and the work speaks for itself. And the report is my testimony. I would not provide information beyond that which is already public in any appearance before Congress.”

Translation: O.K., folks, I’m begging now: Please, please don’t make me testify! I really don’t want to risk getting dragged into the congressional mosh pit and accidentally besmirching my reputation for standing above politics by straightforwardly answering a question. Even if, you know, I do expect everyone to answer my own questions honestly. And even if I’m standing here delivering a very strong hint that Congress should hold impeachment hearings. Heaven forbid that, as the foremost expert on the president’s questionable doings, with expertise earned on the taxpayer’s dime, I should endanger my own image by expressing a forthright view of those doings, even if the future of the Republic might be at stake. If you ignore this plea and subpoena me, expect me to dodge every hard question by referring you to my report. Which, by the way, you should read. Carefully.

Mr. Mueller took a moment to thank everyone “who helped us conduct this investigation in a fair and independent manner. These individuals who spent nearly two years with the special counsel’s office were of the highest integrity.”

Translation: This was not a “witch hunt,” and, contrary to the president’s claims, my team was not a bunch of “angry Democrats.”

He closed by emphasizing “the central allegation of our indictments, that there were multiple, systematic efforts to interfere in our election. And that allegation deserves the attention of every American.”

Translation: This means you, Donald Trump. Time to exhibit some patriotic spirit and defend American democracy."

'Opinion | Decoding Robert Mueller

Wednesday, May 29, 2019

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

Supreme Court allows Indiana to require burial of fetal remains, but not ban certain abortions - ABC News . "The court is sort of continuing its very piecemeal effort to chip away at abortion rights and to make it easier for the states to make abortion inaccessible without actually overruling Roe v Wade," said New York University constitutional law professor Melissa Murray on ABC News' "The Briefing Room."

30 Years After Tiananmen, a Chinese Military Insider Warns: Never Forget - The New York Times

"BEIJING — For three decades, Jiang Lin kept quiet about the carnage she had seen on the night when the Chinese Army rolled through Beijing to crush student protests in Tiananmen Square. But the memories tormented her — of soldiers firing into crowds in the dark, bodies slumped in pools of blood and the thud of clubs when troops bludgeoned her to the ground near the square.

Ms. Jiang was a lieutenant in the People’s Liberation Army back then, with a firsthand view of both the massacre and a failed attempt by senior commanders to dissuade China’s leaders from using military force to crush the pro-democracy protests. Afterward, as the authorities sent protesters to prison and wiped out memories of the killing, she said nothing, but her conscience ate at her.

Now, in the run-up to the 30th anniversary of the June 4, 1989, crackdown, Ms. Jiang, 66, has decided for the first time to tell her story. She said she felt compelled to call for a public reckoning because generations of Chinese Communist Party leaders, including President Xi Jinping, have expressed no remorse for the violence. Ms. Jiang left China this week.

“The pain has eaten at me for 30 years,” she said in an interview in Beijing. “Everyone who took part must speak up about what they know happened. That’s our duty to the dead, the survivors and the children of the future.”

Ms. Jiang’s account has a wider significance: She sheds new light on how military commanders tried to resist orders to use armed force to clear protesters from the square they had taken over for seven weeks, captivating the world.

The students’ impassioned idealism, hunger strikes, rebukes of officials and grandiose gestures like building a “Goddess of Democracy” on the square drew an outpouring of public sympathy and left leaders divided on how to respond.

She described her role in spreading word of a letter from senior generals opposing martial law, and gave details of other letters from commanders who warned the leadership not to use troops in Beijing. And she saw on the streets how soldiers who carried out the party’s orders shot indiscriminately as they rushed to retake Tiananmen Square.

Even after 30 years, the massacre remains one of the most delicate topics in Chinese politics, subjected to a sustained and largely successful effort by the authorities to erase it from history. The party has ignored repeated calls to acknowledge that it was wrong to open fire on the students and residents, and resisted demands for a full accounting of how many died.

The authorities regularly detain former protest leaders and the parents of students and residents killed in the crackdown. A court convicted four men in southwestern China this year for selling bottles of liquor that referred to the Tiananmen crackdown.

Over the years, a small group of Chinese historians, writers, photographers and artists have tried to chronicle the chapters in Chinese history that the party wants forgotten.

But Ms. Jiang’s decision to challenge the silence carries an extra political charge because she is not only an army veteran but also the daughter of the military elite. Her father was a general, and she was born and raised in military compounds. She proudly enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army about 50 years ago, and in photos from her time as a military journalist, she stands beaming in her green army uniform, a notebook in hand and camera hanging from her neck.

She never imagined that the army would turn its guns against unarmed people in Beijing, Ms. Jiang said.

Tiananmen Square on June 2, 1989.Catherine Henriette/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Tiananmen Square on June 2, 1989.Catherine Henriette/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

“How could fate suddenly turn so that you could use tanks and machine guns against ordinary people?” she said. “To me, it was madness.”

Qian Gang, her former supervisor at the Liberation Army Daily, who now lives abroad, corroborated details of Ms. Jiang’s account. Ms. Jiang shared hundreds of yellowing pages of a memoir and diaries that she wrote while trying to make sense of the slaughter.

“More than once I’ve daydreamed of visiting Tiananmen wearing mourning clothes and leaving a bunch of pure white lilies,” she wrote in 1990.

‘The People’s Military’

Ms. Jiang felt a stab of fear in May 1989 when radio and television news crackled with an announcement that China’s government would impose martial law on much of Beijing in an effort to clear student protesters from Tiananmen Square.

The protests had broken out in April, when students marched to mourn the sudden death of Hu Yaobang, a popular reformist leader, and demand cleaner, more open government.

By declaring martial law across urban Beijing, Deng Xiaoping, the party’s leader, signaled that armed force was an option.

Jiang Lin during a military training exercise in the Ningxia region of China in October 1988.

Jiang Lin during a military training exercise in the Ningxia region of China in October 1988.

Researchers have previously shown that several senior commanders resisted using military force against the protesters, but Ms. Jiang gave new details on the extent of the resistance inside the military and how officers tried to push back against the orders.

Gen. Xu Qinxian, the leader of the formidable 38th Group Army, refused to lead his troops into Beijing without clear written orders, and checked himself into a hospital. Seven commanders signed a letter opposing martial law that they submitted to the Central Military Commission that oversaw the military.

“It was a very simple message,” she said, describing the letter. “The People’s Liberation Army is the people’s military and it should not enter the city or fire on civilians.”

Ms. Jiang, eager to spread the word of the generals’ letter, read it over the telephone to an editor at People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s main newspaper, where the staff were disobeying orders to censor news about the protests. But the paper did not print the letter because one of the generals who signed it objected, saying it was not meant to be made public, she said.

Ms. Jiang still hoped that the rumblings inside the military would deter Deng from sending in soldiers to clear the protesters. But on June 3, she heard that the troops were advancing from the west of the city and shooting at people.

The army had orders to clear the square by early on June 4, using any means. Announcements went out warning residents to stay inside.

Family members trying to comfort a woman who had just learned of the death of her son, a student protester killed by soldiers in the Tiananmen massacre.David Turnley/Corbis, via Getty Images

Family members trying to comfort a woman who had just learned of the death of her son, a student protester killed by soldiers in the Tiananmen massacre.David Turnley/Corbis, via Getty Images

‘Any Lie is Possible’

But Ms. Jiang did not stay inside.

She remembered the people she had seen on the square earlier in the day. “Would they be killed?” she thought.

She headed into the city on bicycle to watch the troops come in, knowing that the confrontation represented a watershed in Chinese history. She knew she risked being mistaken for a protester because she was dressed in civilian clothes. But that night, she said, she did not want to be identified with the military.

“This was my responsibility,” she said. “My job was to report major breaking news.”

Ms. Jiang followed soldiers and tanks as they advanced into the heart of Beijing, bursting through makeshift blockades formed with buses and firing wildly at crowds of residents furious that their government was using armed force.

Ms. Jiang stayed close to the ground, her heart pounding as bullets flew overhead. Bursts of gunfire and blasts from exploding gasoline tanks shook the air, and heat from burning buses stung her face.

Near midnight, Ms. Jiang approached Tiananmen Square, where soldiers stood silhouetted against the glow of fires. An elderly gatekeeper begged her not to go on, but Ms. Jiang said she wanted to see what would happen. Suddenly, over a dozen armed police officers bore down on her, and some beat her with electric prods. Blood gushed from her head, and Ms. Jiang fell.

Still, she did not pull out the card that identified her as a military journalist.

“I’m not a member of the Liberation Army today,” she thought to herself. “I’m one of the ordinary civilians.”

Chang’an Avenue beside Tiananmen Square the day after the carnage. Scattered throughout the street are burned remnants of military vehicles destroyed by angry civilians.David Turnley/Corbis, via Getty Images

Chang’an Avenue beside Tiananmen Square the day after the carnage. Scattered throughout the street are burned remnants of military vehicles destroyed by angry civilians.David Turnley/Corbis, via Getty Images

A young man propped her on his bicycle to carry her away, and some foreign journalists rushed her to a nearby hospital, Ms. Jiang said. A doctor stitched up her head wound. She watched, dazed, as the dead and wounded arrived by dozens.

The brutality of that night left her shellshocked.

“It felt like watching my own mother being raped,” she said. “It was unbearable.”

Ms. Jiang has long hesitated to tell her story. The head injury she suffered in 1989 left her with a scar and recurring headaches.

She was interrogated in the months after the 1989 crackdown, and detained and investigated twice in following years over the private memoir that she wrote. She formally left the military in 1996 and has since lived a quiet life, largely ignored by the authorities.

In recalling the events over several interviews in recent weeks, Ms. Jiang’s voice often slowed and her sunny personality seemed to retreat under the shadow of her memories.

Over the years, she said, she waited for a Chinese leader to come forward to tell the country that the armed crackdown was a calamitous error.

But that day never came.

Ms. Jiang said she believed that China’s stability and prosperity would be fragile as long as the party did not atone for the bloodshed.

“All this is built on sand. There’s no solid foundation,” she said. “If you can deny that people were killed, any lie is possible.”

30 Years After Tiananmen, a Chinese Military Insider Warns: Never Forget - The New York Times

Ocasio-Cortez shown among dictators in Fresno Grizzlies' Memorial Day tribute video - The Washington Post

"Among the “enemies of freedom” portrayed in a Memorial Day tribute video at a minor league baseball game: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, former Cuban president Fidel Castro and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

The video, shown between games of the Fresno Grizzlies’ doubleheader Monday, displayed President Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural address on top of patriotic photos and images honoring veterans. A Fresno Bee reporter first pointed out the video on Twitter.

“As for the enemies of freedom, those who are potential adversaries, they will be reminded that peace is the highest aspiration of the American people," Reagan says as a photo of Ocasio-Cortez flashes across the screen between photos of dictators. "We will negotiate for it, sacrifice for it. We will not surrender for it, now or ever.”

A spokesman for Ocasio-Cortez, a self-described Democratic Socialist, declined to comment.

The Grizzlies, the Class AAA affiliate of the Washington Nationals, said in a statement posted on Twitter that they had not seen the full video before it aired. They apologized for not properly vetting it and for taking attention away from veterans.

“A pre-produced video from outside our front office was selected; unfortunately what was supposed to be a moving tribute ended with some misleading and offensive editing, which made a statement that was not our intent and certainly not our opinion,” the Grizzlies wrote of the video that played at Chukchansi Park in Fresno, Calif.

The Grizzlies staff member responsible for the video was “remorseful," team spokesman Paul Braverman told The Washington Post in an email. Braverman confirmed that the team would conduct an internal review to determine how the video bypassed internal controls meant to prevent this kind of incident.

Asked to comment, the Nationals referred to the Fresno club’s statement. The parent club shares no front-office connection with or control over the off-field actions of its affiliate.

Ocasio-Cortez, a high-profile freshman congresswoman, is a frequent target of conservatives’ ire. A Washington Examiner writer tweeted a photo of one of her outfits and commented that it “don’t look like a girl who struggles.” Fox News contributor Mike Huckabee suggested Ocasio-Cortez had been brainwashed by foreign agents to bring down the United States from the inside. And the Ohio Federation of College Republicans recently sent a fundraising email with a subject line calling Ocasio-Cortez “a domestic terrorist.”

“This puts me in danger every time,” the congresswoman wrote on Twitter in reference to the email. “Almost every time this uncalled for rhetoric gets blasted by conserv. grps, we get a spike in death threats to refer to Capitol Police.”

Ocasio-Cortez shown among dictators in Fresno Grizzlies' Memorial Day tribute video - The Washington Post

Monday, May 27, 2019

Memorial Day: America's strained salute to its black veterans - BBC News This is one of the many reasons I swore to myself during my teen years that I would never compromise my personal morality by serving in the US military. Thankfully my draft number was 328. I had already visited the University of Toronto because I was not participating in another of America's hegemonistic wars.

"African Americans have been fighting in conflicts for the US since the Revolutionary War. But despite their sacrifices, the reverence that America usually sets aside for its warriors has not been so forthcoming.

At the end of 2018, US Air Force veteran Janice Jamison was outside the town hall in Augusta before Stacey Abrams, then running for Georgia governor, arrived to talk at an event for a local veterans group for women.

Suddenly Jamison found herself confronted by five white men who began protesting that Abrams didn't understand veterans.

Jamison, who works for the organisation whose members are predominantly African American, tried to reason with the men but found herself being harangued by one man on the subject of veterans' needs.

"I said to him, 'Well, sir, for you to tell me what I need as a veteran, have you ever been in uniform?"

The man - who she later discovered to be a white nationalist - admitted he had not, and appeared visibly embarrassed, she tells the BBC.

Such encounters have some concerned that the current politically and racially charged climate is exacerbating existing problems about how black Americans are treated both in the military and as veterans.

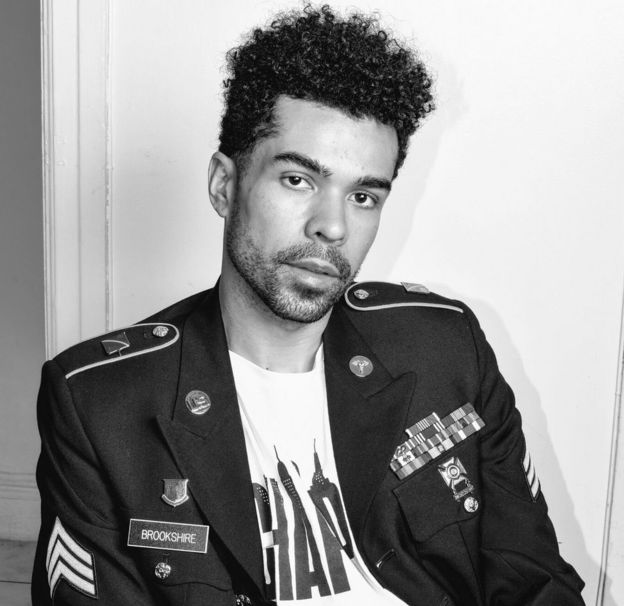

"On paper I made a seamless transition, I got accommodation in New York through a friend, found a job," 26-year-old Richard Brookshire says about leaving the infantry.

But he says over the course of a year his emotional state slowly deteriorated until he couldn't function, and months of depression led to a suicide attempt.

"Part of it was coming to terms with the social and racial climate of the country I was coming back to," explains Brookshire, whose African-American father served in the military as did his mother after emigrating to the US from Haiti.

"I'd been inspired to join and serve under the first black president. I'd even interned for Obama's presidential campaign in Sanford, Florida - and a month after I got back from Afghanistan in 2012 that was where Trayvon Martin was killed."

Image copyrightRICHARD BROOKSHIRE

Image caption

Richard Brookshire wearing his uniform as a civilian

There would be further racially charged tragedies and tensions for Brookshire to contemplate, set against the Black Lives Matter movement emerging in response to Martin's death. In August 2014 riots erupted in Ferguson after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer.

Meanwhile, white supremacists became increasingly bold and public, culminating with the tragedy of Charlottesville in 2017 when a woman was hit and killed by a car that drove into crowds protesting a white supremacist rally.

Brookshire was also unnerved when he discovered how his military career had paralleled that of James Jackson, an Afghanistan veteran and self-proclaimed white supremacist who in 2017 targeted and killed a black homeless man in New York.

"We both went to Fort Leonard Wood, got stationed together in [Germany], deployed to Afghanistan at the same time, got out of the army within a month of each other—it felt like we shadowed one another for those four years," Brookshire says.

"That was the straw that broke the camel's back and had me realising I was emotionally [in trouble] and had to sort [myself out]."

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

Members of the New Black Panther Party rally at a Florida memorial to Trayvon Martin

Brookshire's personal experience as a veteran, coupled with what he saw going on in the country, motivated him to co-found the Black Veterans Project (BVP). It aims to help preserve the historical legacy of America's 2.5 million black veterans while also advocating against racial inequities in the military and post-service.

"The military is the first to say we are a reflection of society. Well, that's the good and the bad," says Kyle Bibby, BVP's other co-founder, who left the Marines as a captain after six years.

"In the military I saw lots of confederate flag tattoos that made me very uncomfortable, and the sorts of personalities that you might expect with them."

He says that a sense of neglect or "assumptions being made about me" made him "deeply examine my blackness."

Although it is unclear where exactly the Memorial Day tradition originated, Bibby notes that one of the earliest commemorations followed the Confederate surrender, when recently freed slaves gathered on 1 May, 1865, to consecrate a burial site for 250 Union soldiers who had died in the fight to grant African Americans their freedom.

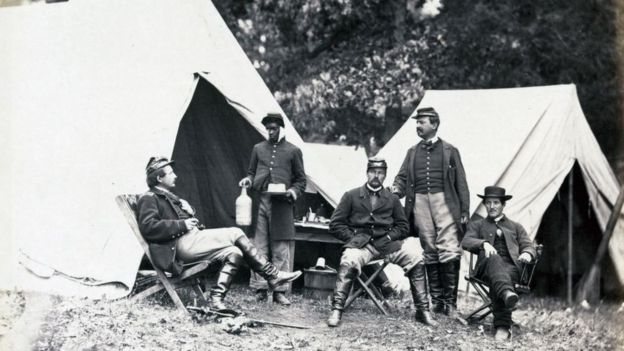

During the Civil War, more than 180,000 African Americans wore the Union Army blue.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

A black orderly serves drinks to Union officers during the Civil War

Another 30,000 served in the Navy, and 200,000 served as workers in military-support roles. More than 33,000 were killed.

When World War I broke out, 380,000 black men heeded the call of the black intellectual WEB Du Bois to enlist in the segregated army in the hope that doing so would empower greater opportunities for black Americans on the home front.

Today, black Americans account for 17% of America's 1,340,533 active-duty personnel - including those serving in the US Coast Guard - according to the Pew Research Center.

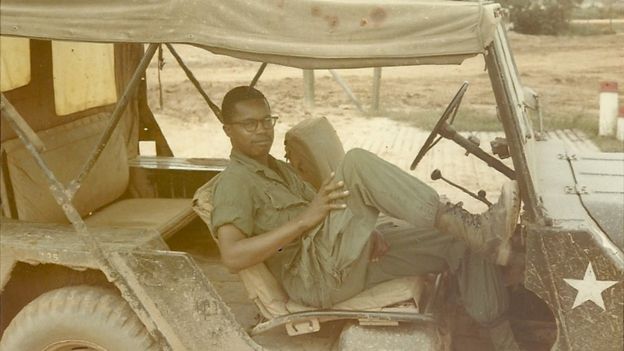

"The military has always been popular in the black community," says Paul Matthews, who served as a platoon surgeon in Vietnam before founding Houston's Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, which examines the role of African-American soldiers during US military history.

"In the 1960s, when you graduated from high school you either went to college or to the military. It was Frederick Douglass who said that if you put a uniform on a black man and a musket on his shoulder then you could not stop him being a citizen and a man."

Image copyrightPAUL MATTHEWS

Image caption

Paul Matthews as a lieutenant in jeep at Camp Red Devil, 5th Infantry Div. Quang Tri, Vietnam, 1968

Such hopes haven't been borne out by the data.

Protect Our Defenders, an advocacy group, released a 2017 report highlighting how black service members were treated more harshly by the military's judicial system.

Black soldiers were 61% more likely than white soldiers to face court martial, the military judicial proceeding for more serious offenses. That percentage was 40% for black sailors and 32% for black Marines.

Black airmen were 71% more likely than whites in the Air Force to face court martial or non-judicial punishment, discipline meted out for less serious offenses.

"I seem to be getting inundated with black female officers who are being disciplined for dumb stuff," says Coretta Gray, who spent 13 years as an officer in the Air Force Judge Advocate General's Corps, the military's branch for military justice and military law, and continues to consult on cases.

"Often those sorts of issues are sorted out at unit level before it has to go anywhere, and I'd contend that usually whites get the benefit of that more than blacks," Gray says.

Image copyrightCORETTA GRAY

Image caption

Coretta Gray says black women are disproportionally disciplined

"It may well be unconscious bias, as opposed to anything institutional, as you tend to help those within your social group and who you are more familiar with."

But she also suspects that the current mood in America has something to do with why she is seeing an increase in these types of disciplinary cases.

"People are feeling more emboldened to act out their biases," Gray says. "It's an inflection moment - there's this atmosphere emboldening people to show who's in charge and how they are going to handle things."

Unequal justice for black troops is likely influenced by a lack of diversity in the military hierarchy, observers note. In 2016, about 78% of military officers were white, while 8% were black.

At the same time, many black veterans say that the military does a far better job of embracing egalitarianism than the rest of US society.

"Growing up in the '80s in Connecticut and New York, you didn't see many prominent black people," says 38-year-old Sadiki Harriott, who is originally from Jamaica, and served eight years in the US army as an IT specialist.

"There were no business owners - people did things like my dad who was a plumber. But once I got into the military I saw all types of races in leadership roles," he adds.

"One of the most influential people in my life was Master Sergeant Alan Dewitt - he was the first black person who showed me what I might achieve: he was an impressive guy; he got a degree in the military and drove a Mercedes."

Media captionWhat makes a hero? Part 1: Thank you for your service

Due to his IT skillset, Harriott says he had little trouble transitioning to the civilian realm, landing a well-paid job in cyber security. But his veteran success story is only one side of the coin.

Bibby notes how many blacks leaving the military often go in two totally different directions: some are boosted into the middle class and a better station than they had before, while others fall entirely off the ladder.

Today roughly 45% of all homeless veterans are African American, despite only accounting for 10.4% of the US veteran population, according to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates that 40,056 veterans are homeless on any given night.

"A lot of it has to do with education. If you joined before finishing high school and leave the military before doing your 20 years, the chances of not being successful when you come out are higher," Matthews says.

"And if you come back to an urban environment, there aren't many jobs, there's just one VA [Veterans Affairs] centre where it's hard to get appointments. That adds to negative experiences."

More on African-American history

•Should black Americans get slavery reparations?

•Last survivor of US slave ships discovered

The black soldiers who brought jazz to Europe

Heart and soul: Portraits of black American history

As with African American experiences in the civilian realm, there is a precedent for black veterans being treated differently.

"There's been a historical consistency in black veterans being treated badly ever since the Red Summer," says Bibby, noting the period following WWI when many African Americans returned home from the war with a new confidence and assertiveness, which often didn't go now well with many whites.

Image copyrightKYLE BIBBY

Image caption

Kyle Bibby was deployed to Afghanistan

More than twenty "anti-black riots" erupted in major cities throughout the nation in 1919, including Houston, Chicago and Washington, DC.

"No one was more at risk of experiencing violence and targeted racial violence than black veterans," concludes the Equal Justice Initiative report, Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans, which investigated racial violence and terror in America between 1877 and 1950.

In a 1917 speech on the Senate floor, Mississippi Senator James Vardaman said the return of black veterans to the South would "inevitably lead to disaster", and he warned that once you "impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag" and "inflate his untutored soul with military airs", it risked the conclusion that "his political rights must be respected".

Image copyrightLIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Image caption

Formation of black soldiers, after Spanish-American War, circa 1899

The push back could also be more subtle.

Sergeant William Butler was an African-American soldier who returned from France at the top of a list of men nominated for a Medal of Honor, after single-handedly taking on a German raiding party returning from attacking an America trench and capturing prisoners.

Butler, a slight 27-year-old, killed 10 Germans, took a German lieutenant prisoner, freed all the American prisoners and hustled them back to the safety of the American trenches.

But Butler didn't get the medal.

In 1947 he hanged himself and is now buried in Arlington National Cemetery (with a typo on his tombstone). Recently a Maryland senator introduced the World War I Valor Medals Review Act, legislation that would require the Defence Department to look at forgotten black war heroes like Butler.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

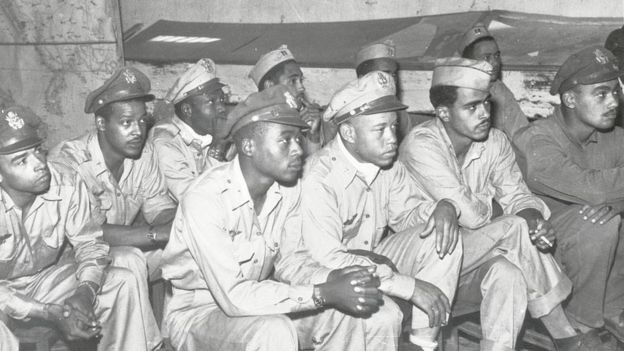

African-American World War II pilots being briefed to fly a mission over Italy

America's relationship with its veterans has long been volatile, even without the added factor of race.

The unpopularity of the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s meant many veterans returned to indifference or open hostility.

Collective guilt about that treatment heavily influenced the more contemporary "thank you for your service" culture that persists in America, in marked contrast to the treatment of veterans in the likes of the UK, where responses to veterans are typically more muted.

But veterans have sensed a growing apathy towards "America's longest war" in Afghanistan and the conflict in Iraq, and in turn towards those who served there.

"When the war was at its apex, from around 2003 - 2009, if you were in uniform, people would thank you," says Joe Geeter, a former gunnery sergeant who served for 25 years, and now public relations officer for the Montford Point Marines, a veteran's organisation founded to memorialise the first African Americans to serve in the United States Marine Corps.

Image copyrightTONY BYRD

Image caption

Joe Geeter at his Montford Point Marines office, with military memorabilia on the walls

"Now the whole climate has changed, often people ignore you," he adds. "Even at Veterans Affairs, I encountered staff who would say things like you are acting too entitled."

In 2018, a video went viral showing two uniformed Army Reserve black female captains - one of them pregnant - being confronted in a Georgia restaurant by a 71-year-old white woman and her son after a parking-space dispute escalated in front of shocked diners.

The captains, who had served a total of 27 years between them, were called "black lesbian bitches" by the son while his mother was arrested for assault after striking one of the captains in the face during the altercation.

"While I don't think there should be special treatment, at the same time I take pride in the fact that I served and that my role was important," Janice Jamison, the US Air Force veteran says.

African Americans have been fighting in conflicts for the US since the Revolutionary War. But despite their sacrifices, the reverence that America usually sets aside for its warriors has not been so forthcoming.

At the end of 2018, US Air Force veteran Janice Jamison was outside the town hall in Augusta before Stacey Abrams, then running for Georgia governor, arrived to talk at an event for a local veterans group for women.

Suddenly Jamison found herself confronted by five white men who began protesting that Abrams didn't understand veterans.

Jamison, who works for the organisation whose members are predominantly African American, tried to reason with the men but found herself being harangued by one man on the subject of veterans' needs.

"I said to him, 'Well, sir, for you to tell me what I need as a veteran, have you ever been in uniform?"

The man - who she later discovered to be a white nationalist - admitted he had not, and appeared visibly embarrassed, she tells the BBC.

Such encounters have some concerned that the current politically and racially charged climate is exacerbating existing problems about how black Americans are treated both in the military and as veterans.

"On paper I made a seamless transition, I got accommodation in New York through a friend, found a job," 26-year-old Richard Brookshire says about leaving the infantry.

But he says over the course of a year his emotional state slowly deteriorated until he couldn't function, and months of depression led to a suicide attempt.

"Part of it was coming to terms with the social and racial climate of the country I was coming back to," explains Brookshire, whose African-American father served in the military as did his mother after emigrating to the US from Haiti.

"I'd been inspired to join and serve under the first black president. I'd even interned for Obama's presidential campaign in Sanford, Florida - and a month after I got back from Afghanistan in 2012 that was where Trayvon Martin was killed."

Image copyrightRICHARD BROOKSHIRE

Image copyrightRICHARD BROOKSHIREThere would be further racially charged tragedies and tensions for Brookshire to contemplate, set against the Black Lives Matter movement emerging in response to Martin's death. In August 2014 riots erupted in Ferguson after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer.

Meanwhile, white supremacists became increasingly bold and public, culminating with the tragedy of Charlottesville in 2017 when a woman was hit and killed by a car that drove into crowds protesting a white supremacist rally.

Brookshire was also unnerved when he discovered how his military career had paralleled that of James Jackson, an Afghanistan veteran and self-proclaimed white supremacist who in 2017 targeted and killed a black homeless man in New York.

"We both went to Fort Leonard Wood, got stationed together in [Germany], deployed to Afghanistan at the same time, got out of the army within a month of each other—it felt like we shadowed one another for those four years," Brookshire says.

"That was the straw that broke the camel's back and had me realising I was emotionally [in trouble] and had to sort [myself out]."

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESBrookshire's personal experience as a veteran, coupled with what he saw going on in the country, motivated him to co-found the Black Veterans Project (BVP). It aims to help preserve the historical legacy of America's 2.5 million black veterans while also advocating against racial inequities in the military and post-service.

"The military is the first to say we are a reflection of society. Well, that's the good and the bad," says Kyle Bibby, BVP's other co-founder, who left the Marines as a captain after six years.

"In the military I saw lots of confederate flag tattoos that made me very uncomfortable, and the sorts of personalities that you might expect with them."

He says that a sense of neglect or "assumptions being made about me" made him "deeply examine my blackness."

Although it is unclear where exactly the Memorial Day tradition originated, Bibby notes that one of the earliest commemorations followed the Confederate surrender, when recently freed slaves gathered on 1 May, 1865, to consecrate a burial site for 250 Union soldiers who had died in the fight to grant African Americans their freedom.

During the Civil War, more than 180,000 African Americans wore the Union Army blue.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESAnother 30,000 served in the Navy, and 200,000 served as workers in military-support roles. More than 33,000 were killed.

When World War I broke out, 380,000 black men heeded the call of the black intellectual WEB Du Bois to enlist in the segregated army in the hope that doing so would empower greater opportunities for black Americans on the home front.

Today, black Americans account for 17% of America's 1,340,533 active-duty personnel - including those serving in the US Coast Guard - according to the Pew Research Center.

"The military has always been popular in the black community," says Paul Matthews, who served as a platoon surgeon in Vietnam before founding Houston's Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, which examines the role of African-American soldiers during US military history.

"In the 1960s, when you graduated from high school you either went to college or to the military. It was Frederick Douglass who said that if you put a uniform on a black man and a musket on his shoulder then you could not stop him being a citizen and a man."

Image copyrightPAUL MATTHEWS

Image copyrightPAUL MATTHEWSSuch hopes haven't been borne out by the data.

Protect Our Defenders, an advocacy group, released a 2017 report highlighting how black service members were treated more harshly by the military's judicial system.

Black soldiers were 61% more likely than white soldiers to face court martial, the military judicial proceeding for more serious offenses. That percentage was 40% for black sailors and 32% for black Marines.

Black airmen were 71% more likely than whites in the Air Force to face court martial or non-judicial punishment, discipline meted out for less serious offenses.

"I seem to be getting inundated with black female officers who are being disciplined for dumb stuff," says Coretta Gray, who spent 13 years as an officer in the Air Force Judge Advocate General's Corps, the military's branch for military justice and military law, and continues to consult on cases.

"Often those sorts of issues are sorted out at unit level before it has to go anywhere, and I'd contend that usually whites get the benefit of that more than blacks," Gray says.

Image copyrightCORETTA GRAY

Image copyrightCORETTA GRAY"It may well be unconscious bias, as opposed to anything institutional, as you tend to help those within your social group and who you are more familiar with."

But she also suspects that the current mood in America has something to do with why she is seeing an increase in these types of disciplinary cases.

"People are feeling more emboldened to act out their biases," Gray says. "It's an inflection moment - there's this atmosphere emboldening people to show who's in charge and how they are going to handle things."

Unequal justice for black troops is likely influenced by a lack of diversity in the military hierarchy, observers note. In 2016, about 78% of military officers were white, while 8% were black.

At the same time, many black veterans say that the military does a far better job of embracing egalitarianism than the rest of US society.

"Growing up in the '80s in Connecticut and New York, you didn't see many prominent black people," says 38-year-old Sadiki Harriott, who is originally from Jamaica, and served eight years in the US army as an IT specialist.

"There were no business owners - people did things like my dad who was a plumber. But once I got into the military I saw all types of races in leadership roles," he adds.

"One of the most influential people in my life was Master Sergeant Alan Dewitt - he was the first black person who showed me what I might achieve: he was an impressive guy; he got a degree in the military and drove a Mercedes."

Due to his IT skillset, Harriott says he had little trouble transitioning to the civilian realm, landing a well-paid job in cyber security. But his veteran success story is only one side of the coin.

Bibby notes how many blacks leaving the military often go in two totally different directions: some are boosted into the middle class and a better station than they had before, while others fall entirely off the ladder.

Today roughly 45% of all homeless veterans are African American, despite only accounting for 10.4% of the US veteran population, according to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates that 40,056 veterans are homeless on any given night.

"A lot of it has to do with education. If you joined before finishing high school and leave the military before doing your 20 years, the chances of not being successful when you come out are higher," Matthews says.

"And if you come back to an urban environment, there aren't many jobs, there's just one VA [Veterans Affairs] centre where it's hard to get appointments. That adds to negative experiences."

More on African-American history

- •Should black Americans get slavery reparations?

- •Last survivor of US slave ships discovered

- The black soldiers who brought jazz to Europe

- Heart and soul: Portraits of black American history

As with African American experiences in the civilian realm, there is a precedent for black veterans being treated differently.

"There's been a historical consistency in black veterans being treated badly ever since the Red Summer," says Bibby, noting the period following WWI when many African Americans returned home from the war with a new confidence and assertiveness, which often didn't go now well with many whites.

Image copyrightKYLE BIBBY

Image copyrightKYLE BIBBYMore than twenty "anti-black riots" erupted in major cities throughout the nation in 1919, including Houston, Chicago and Washington, DC.

"No one was more at risk of experiencing violence and targeted racial violence than black veterans," concludes the Equal Justice Initiative report, Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans, which investigated racial violence and terror in America between 1877 and 1950.

In a 1917 speech on the Senate floor, Mississippi Senator James Vardaman said the return of black veterans to the South would "inevitably lead to disaster", and he warned that once you "impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag" and "inflate his untutored soul with military airs", it risked the conclusion that "his political rights must be respected".

Image copyrightLIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Image copyrightLIBRARY OF CONGRESSThe push back could also be more subtle.

Sergeant William Butler was an African-American soldier who returned from France at the top of a list of men nominated for a Medal of Honor, after single-handedly taking on a German raiding party returning from attacking an America trench and capturing prisoners.

Butler, a slight 27-year-old, killed 10 Germans, took a German lieutenant prisoner, freed all the American prisoners and hustled them back to the safety of the American trenches.

But Butler didn't get the medal.

In 1947 he hanged himself and is now buried in Arlington National Cemetery (with a typo on his tombstone). Recently a Maryland senator introduced the World War I Valor Medals Review Act, legislation that would require the Defence Department to look at forgotten black war heroes like Butler.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

America's relationship with its veterans has long been volatile, even without the added factor of race.

The unpopularity of the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s meant many veterans returned to indifference or open hostility.

Collective guilt about that treatment heavily influenced the more contemporary "thank you for your service" culture that persists in America, in marked contrast to the treatment of veterans in the likes of the UK, where responses to veterans are typically more muted.

But veterans have sensed a growing apathy towards "America's longest war" in Afghanistan and the conflict in Iraq, and in turn towards those who served there.

"When the war was at its apex, from around 2003 - 2009, if you were in uniform, people would thank you," says Joe Geeter, a former gunnery sergeant who served for 25 years, and now public relations officer for the Montford Point Marines, a veteran's organisation founded to memorialise the first African Americans to serve in the United States Marine Corps.

Image copyrightTONY BYRD

Image copyrightTONY BYRD"Now the whole climate has changed, often people ignore you," he adds. "Even at Veterans Affairs, I encountered staff who would say things like you are acting too entitled."

In 2018, a video went viral showing two uniformed Army Reserve black female captains - one of them pregnant - being confronted in a Georgia restaurant by a 71-year-old white woman and her son after a parking-space dispute escalated in front of shocked diners.

The captains, who had served a total of 27 years between them, were called "black lesbian bitches" by the son while his mother was arrested for assault after striking one of the captains in the face during the altercation.

"While I don't think there should be special treatment, at the same time I take pride in the fact that I served and that my role was important," Janice Jamison, the US Air Force veteran says.

"I joined two months out of high-school when I was 18, and all my kids have known is war - my eldest son, who is 17 now, was born just after 9/11."

Image copyrightJANICE JAMISON

Image copyrightJANICE JAMISONBibby says he struggles with the mythologising of veterans that sometimes occurs in public discourse, and with "the cult of worship built around the uniform and often perpetuated by profiteers and politicians who know nothing of military service".

"But," Bibby emphasises, "I think there should be better acknowledgment of the fact that, one, veterans made a sacrifice, two, many are coming to terms with real trauma, and, three, though we like to think the military does things better than society, there are still the same issues happening like racism and sexism."

For any black veteran, there is the added complication of squaring your military service for your country with how many of your fellow citizens perceive your blackness.

"I'd just got back from Iraq and was visiting Austin, Texas, driving around in a friend's nice BMW," says Harriott, the former Army IT specialist.

He describes how he pulled into a busy shopping plaza in the middle of the day to ask for directions.

"I pulled up to a white lady and started to say, 'Excuse me, could you tell me…' but she was running to her car" he says.

"I'd been applauded when I arrived at the airport in my uniform."

Memorial Day: America's strained salute to its black veterans - BBC News

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)